Thailand encroaches past contested zones as conflict settles

And Chen Zhi is deported to China

Hello and a happy new year to the Herd. It has been a quiet-ish start to the new year, of course, discounting the potentially illegal actions of a crumbling superpower attempting to take control of the largest oil deposits in the world. We digress.

The China-brokered ceasefire from December 2025 is holding for the most part, with only a small explosion reported from the border in Preah Vihear’s Chong Bok region (where the conflict ignited in July 2026). Thankfully this did not trigger a restart of hostilities. Of course, both countries are now in a pitched PR battle aimed at both domestic and international audiences, with Thailand’s ruling party looking to extract every bit of prevailing nationalistic sentiment ahead of elections next month. (Recent polling suggests this might not be working as well as they hoped).

On the domestic front, Prime Minister Hun Manet has finally addressed the conflict in several lengthy Facebook posts and a speech — while sidestepping any discussion of the realities on the ground. He has insisted that Cambodia did not surrender, nor was it trading its territorial integrity for peace. In a special broadcast address to the nation, which was supposed to list out rehabilitation and restoration plans, Manet didn’t offer any path forward beyond leaning on banks and MFIs to find ways to ease the debt burden on displaced communities. Good luck, sir. Good luck.

His father, Hun Sen, also emerged from the Hun cave to inspect aid operations at his daughter’s Bayon TV television studios, where he wandered on to a news set, the production control room and even controlled a camera during a live interview. (Providing us with great photos like this one).

Apart from that, the big man only posted peace songs, marked Peace Day on December 29 and shared documents and content from other accounts. The Cambodian People’s Party also made the unusual move of canceling the January 7 “Victory Day” celebration this year — a controversial holiday that commemorates the fall of the Khmer Rouge — in light of the conflict. Both political leaders also made it a point to organize public events with the 18 released prisoners of war.

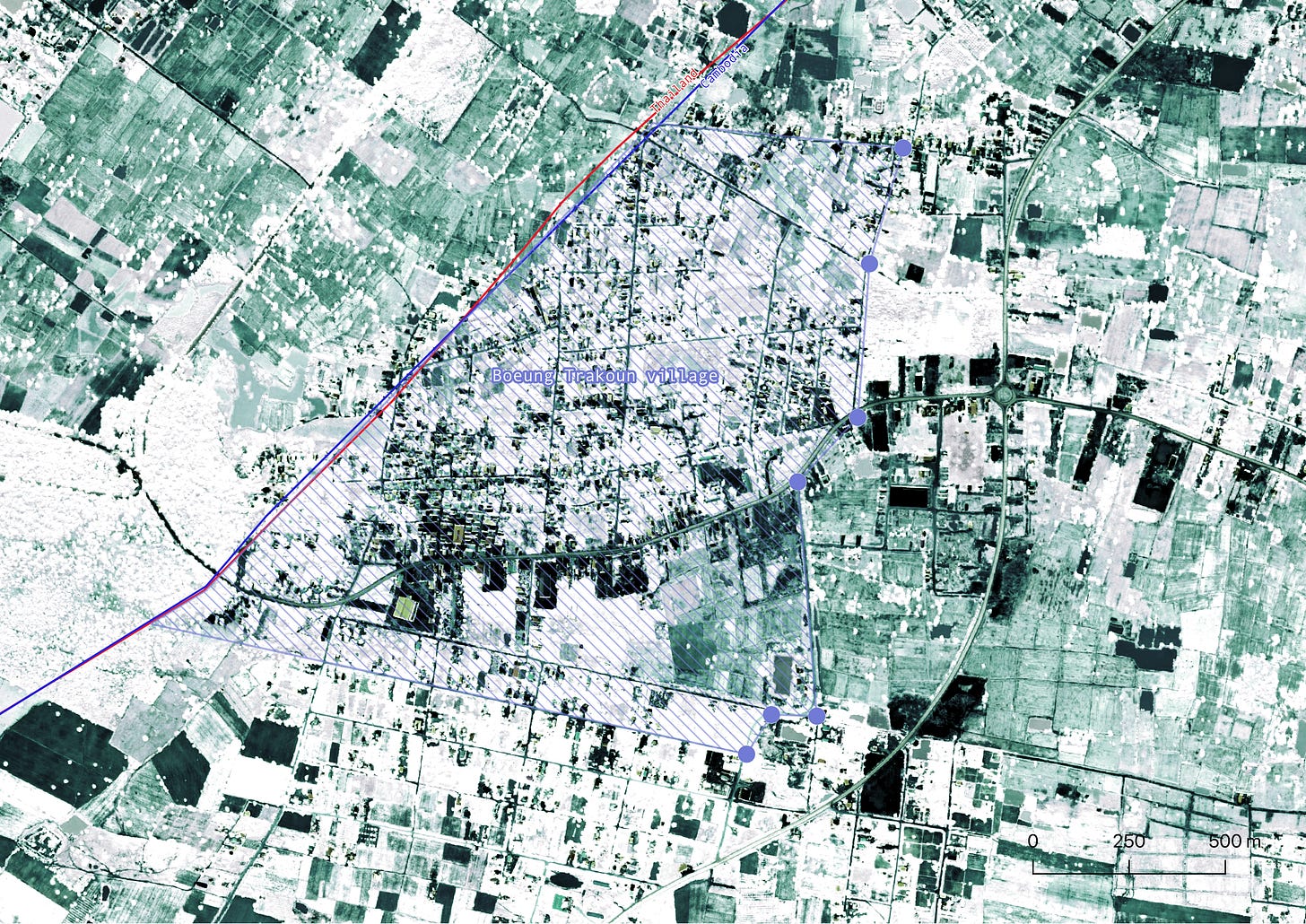

Back to the border. Within days of the ceasefire, Cambodia’s border committee said they were resuming border demarcation activities at the two contested villages of Chouk Chey and Prey Chan, the Boeung Trakoun border checkpoint to the north, and scam hotbed Thmor Da. Photos started to emerge on social media from both sides of the border showing positions held by the Cambodians and Thais.

In the weeks since, we have collated information about every attack, verified photos and videos posted to social media and elsewhere, and combed through officially reported positions of militaries. Altogether, we’re using this info to take a closer look to determine which military gained or lost ground during the 20 days of conflict. Then we’ll talk about everyone’s favorite ousted scam boss: Chen Zhi.

This is a big one, so let’s get into it.

P.S: Given the size of the maps, this post might be clipped on email but you can open it in your browser or read the post on Kouprey’s Substack.

Land Lost

To recap: By July 28, when the first ceasefire started, the conflict was largely confined to border areas in Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear provinces. At that time, Thailand’s major gains were Phnom Trob, a mountain overlooking the access to Preah Vihear temple. Thailand also claimed that it had control over the contested Ta Moan Thom temple. (As a reminder, the separate Ta Moan Touch temple is effectively on the Thai side of the border, and has not seen any reported military action over the two periods of active conflict. Read our update from August here).

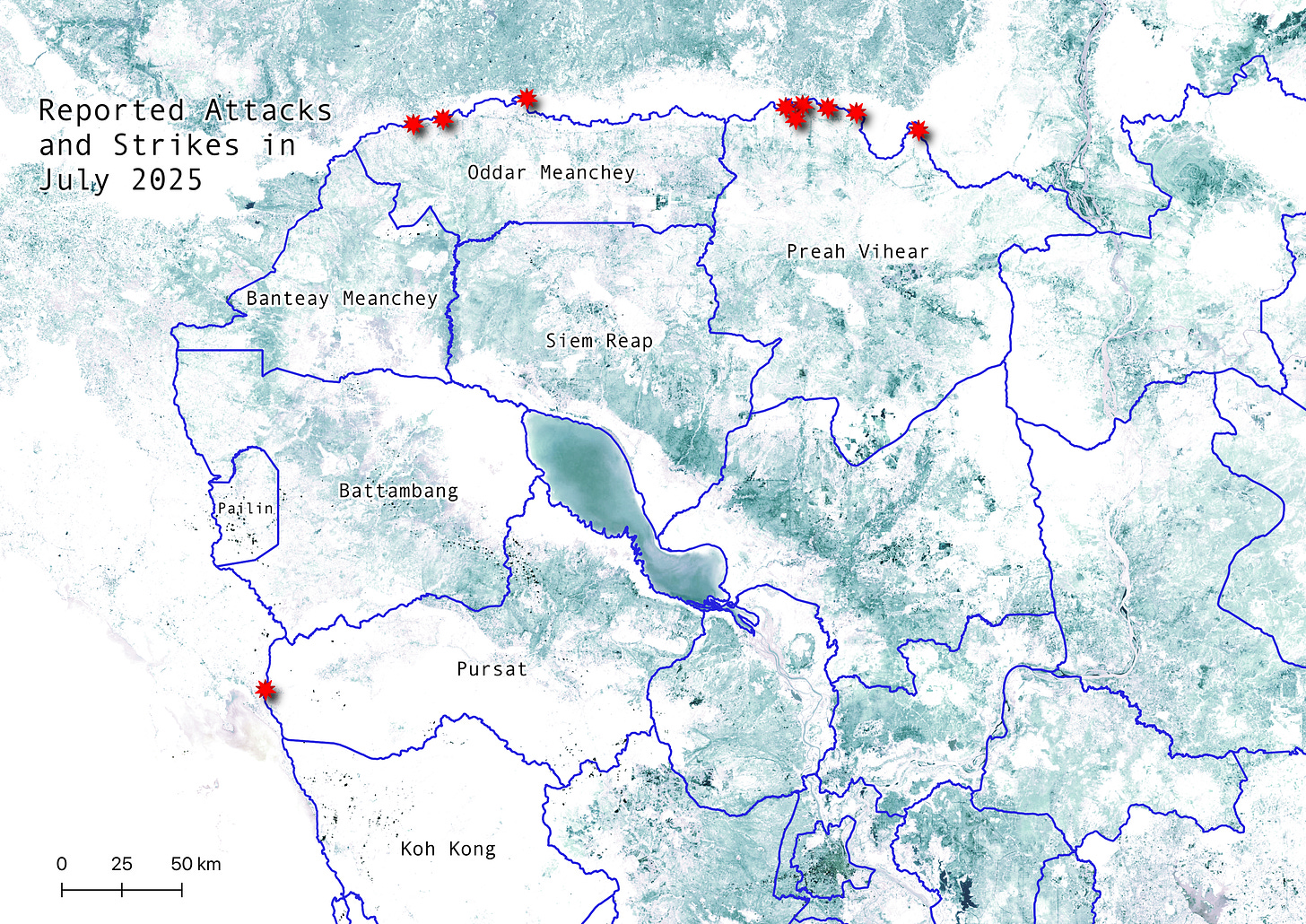

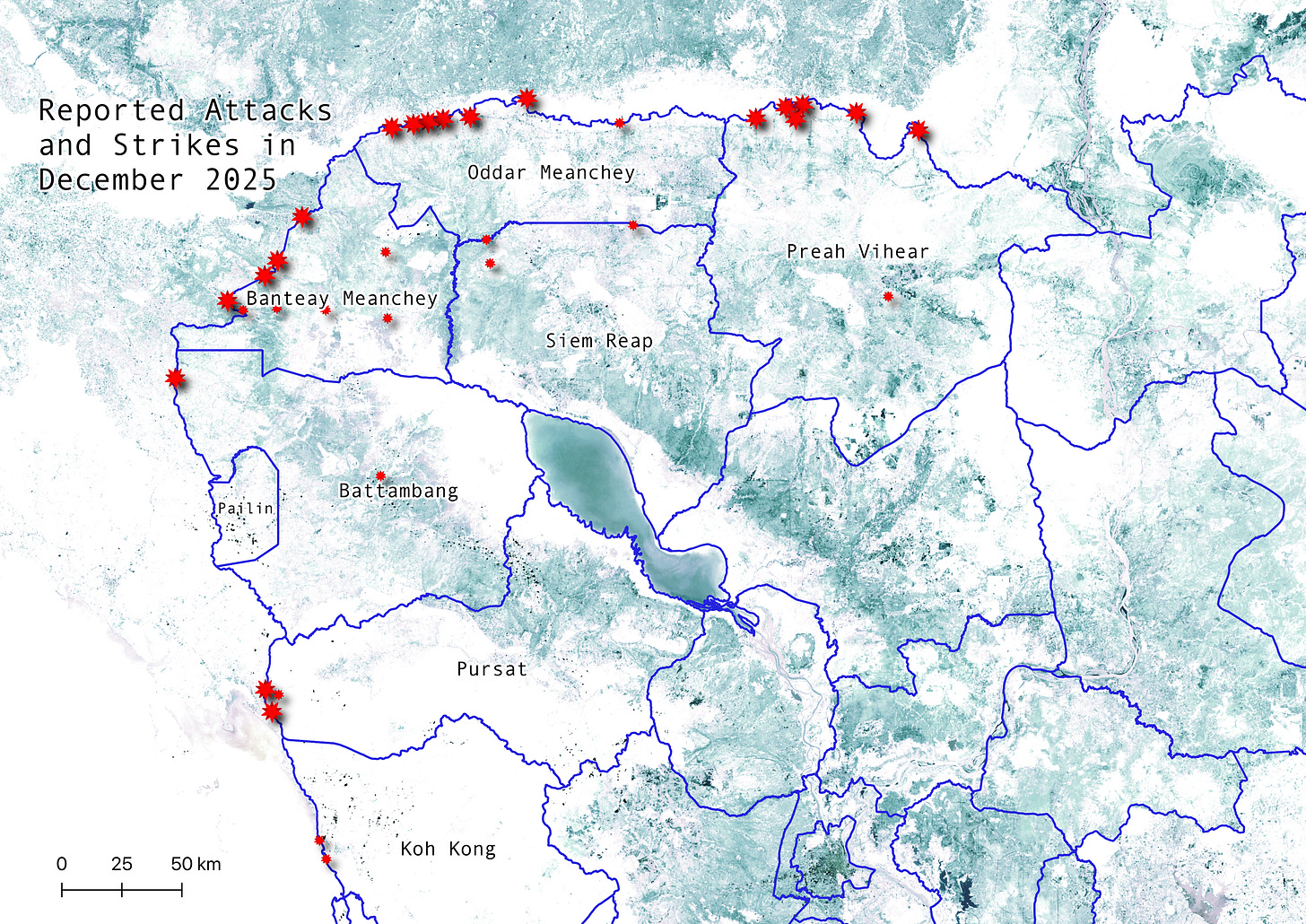

The two maps below - the first from July and the second from December - show significant uptick in strikes and attacks in the conflict’s second iteration. More strikes occurred by volume in Oddar Meanchey and Preah Vihear provinces, with new targets in Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, Pursat and even Koh Kong.

Thmor Da casino and SEZ

The Thmor Da special economic zone in Pursat province — a notorious scam destination owned by Cambodian tycoon Try Pheap — saw heavy shelling and Thai troops on the ground in December. Using two videos posted on social media (see video 1 and video 2), Kouprey geolocated razor wire placed by the Thai military that seemingly cuts off the casino, an abandoned building next to it, and a section of developed property that appears to be villas.

Those villas were also the site of a Thai strike (marked in red) that Fresh News described as the homes of “Chinese investors.” (Read: scam compounds). The other red strike shows the abandoned building next to the casino.

The positioning of the barbed wire in parts of Thmor Da indicates that Thailand has likely entered Cambodian territory beyond its own claimed border line (shown in red) which at its most extreme only included the area approaching the casino, not encompassing it.

Chouk Chey, Prey Chan and Boeung Trakoun

Now for the more interesting “invasion” claims. Chouk Chey and Prey Chan villages in Banteay Meanchey province have been at the center of clashes during both iterations of the conflict. After firing stopped in July, the Thai military placed rubber tire walls and razor wire across small sections of the villages that Thailand claimed was part of their sovereign land. These sites saw unarmed villagers protest against armed Thai soldiers as the Cambodian police and military stood by and watched.

After the December clashes, Thailand has fortified its claim in Chouk Chey village, again beyond its own boundary claims. Using images and drone footage posted by a former CNRP politician (also a strong border hawk), we were able to identify two locations (marked in orange) where the Thai military has shipping containers and razor wire to create high barriers. The map below shows how these markers have effectively cordoned off the entire village from Cambodia.

This trio of villages comprise the only site where Cambodian government has acknowledged land loss, providing the public maps to show how much land is within their neighbor’s control (marked in purple). We have not seen any photos or videos to verify the other locations the government alleges Thailand has occupied in Chouk Chey, but the positions seem plausible based on our orange markers.

We found little evidence of what is happening on the ground at Prey Chan and have had to rely on a government map, reproduced below, showing Thailand’s alleged land occupation in purple.

And last in this group of villages is Boeung Trakoun, an area located further north where intense firing played out at the border checkpoint. Although we collated images of damaged buildings and destroyed government offices, we have not seen any images of on-the-ground positions held by either military. Again, here’s a reproduced government map showing Thailand’s alleged position in purple.

Note: These government maps contain discrepancies in their claimed border lines, with some placing Thai border lines further inside Cambodia than the records we have previously accessed from the UN.

Ta Krabey temple

Next up, we have the Ta Krabey temple site in Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey province, which is fully controlled by the Thai military. In effect, Thailand now occupies all three contested temples along the border: Ta Krabey, Ta Moan Thom and Ta Moan Touch.

Ta Krabey seems to have taken a battering, with the Thais making significant gains at the ridge near the temple, which provides high ground. Satellite imagery shows new clearings just south of the temple abutting a cliff face.

This suggests that the Thai military has control of the entire hilltop and has pushed the Cambodian military down into the valley, like they did at Phnom Trob. We don’t have photos from the ridge itself, but the fact the Thai PM Anutin visited the temple site recently makes us suspect they have a solid buffer around the temple to have approved the visit.

O’Smach border town

Finally, let’s turn to O’Smach in Oddar Meanchey, which saw heavy shelling in December. The town is home to the US-sanctioned O’Smach Resort, a thriving alleged scam compound owned by Cambodian tycoon Ly Yong Phat.

We were only able to locate a few videos of razor wire laid out on the road leading to the border checkpoint. This would in effect block access to the front entrance of O’Smach Resort, but we are sure the bosses will find their way around if they’re so inclined. Alternatively, LYP can always move his alleged scam operations to his other resort and the adjacent alleged scam megacomplex in Koh Kong.

We’ll keep scouring the news and social media to get more information about what’s happening on the ground, and if any Herd members want to send us specifics, we’re happy to review them.

Prince and Princeling Besieged

The saga of prolific scamlord Chen Zhi — whose fall we previously covered here and here — took another turn when China arrested and extradited Chen last week.

This is, without a doubt, the deepest anti-scam intervention China has taken in Cambodia thus far.

Chinese media, led by state China Central Television, have presented a unified narrative of his arrest, broadcasting video of Chen being led off a plane with a black bag over his head, sandwiched by two police officers wearing helmets. CCTV also blasted this statement from state security services: “The public security organs solemnly warn criminals to recognise the situation, stop their crimes before it’s too late, and immediately surrender themselves to the authorities to receive lenient treatment.” In other words, they’re going after Chen’s broader network.

Chen’s extradition has triggered a roiling scam shake-up across Cambodia, with compounds emptying in Chrey Thom, Bavet, Tbong Khmum, Kampot and Sihanouk, including well-known scam hubs Huangle, Jincai and Kaibo 2. (As always, head to Cyber Scam Monitor for granular updates).

Videos have shown people leaving compounds en masse by foot, climbing out of windows and streaming down roadways. One mid-level scam worker told us he has been hauled from province to province in the past three days, outpacing Chinese and Cambodian police raiding buildings after scammers flee.

It’s not clear, exactly, where these operations will land or how this might end, and we’d caution anyone against making big pronouncements. But it’s worth noting that in addition to everything else, China has also flown in Liu Zhongyi, the anti-scam czar who led mass releases in Myanmar last year.

Let’s take a step back for a minute to talk about China’s broader messaging here. Mao Ning, one of China’s foreign ministry spokespeople, told reporters in the wake of Chen’s arrest that “China stands ready to enhance law enforcement cooperation with neighboring countries, including Cambodia, and to jointly protect the safety of people’s life and property, and to maintain the order of exchanges and cooperation among the countries in the region.”

On the one hand, kind of a meh statement. On the other, this is actually a useful insight into how China is presenting its role in the region, especially after brokering the only ceasefire deal that has so far stuck. China views itself as a forever member of the developing world, and thus ready to stand united against the West’s meddlesome interventions — but also a global superpower that won’t stand for increasingly embarrassing and frustrating behavior in its own backyard.

That said, China has been well-aware of Chen for years. So perhaps the more interesting question isn’t why, but why now? We’ve seen quite a bit of speculation on this, and we aren’t China experts, but a few thoughts: We’ve previously said that China has tended to intervene in scamming where it’s 1) politically expedient and 2) not too difficult to pull off.

Clearly, something shifted in the Chinese state’s assessment of scamming in Cambodia to make arresting Chen politically expedient. (It probably never would have been too difficult, though perhaps the ceasefire gave China more leverage). And while Chen’s US indictment seems like an obvious tipping point, we wouldn’t be surprised if this shift had been under way for some time as Cambodia has continued expanding the industry — just as China gained more meaningful success in its anti-scam campaign.

Although it’s tempting to speculate about the future of scamming more broadly, the reality is that very few people aside from Chen and his fellow bosses actually know the makeup of his company operations and who might fill this vacuum, if anyone, and no one except Liu Zhongyi can tell us what China will do next.

Plus, we don’t have many comparable examples: Although the 2022 She Zhijiang arrest in Myanmar proved that arresting a single figurehead doesn’t do much, in this case, China has promised to attack Chen’s whole network. In that sense, perhaps this episode is best compared to the scorched-earth Operation 1027 arrests that effectively ended scamming in Myanmar’s Kokang — but there again, the political economy was completely different, and scamming arguably dried up not because of China’s arrests but because the ethnic armed organization that took over pinned its local legitimacy on keeping scamming out of its territories.

In other words, this is a new one. Let’s wait and see.

Our Substack overlords have cut us off here, so if anyone made it this far, see you next week!

Great post thank you. Would just add that She Zhijiang was arrested in Thailand, and it certainly affected Yatai’s operations in Shwekokku, although there are other Yatai businesses in Manila still operating. With his deportation from Thailand to China and selective demolitions and raids in Shwekokku I would guess his network is significantly damaged now.