We Mapped the Thai-Cambodian Border Disputes

And other stories that were eclipsed by the border flare-up.

The border dispute between Cambodia and Thailand isn’t dying down: If anything, Senate President Hun Sen seems to be ramping up the rhetoric and making moves that can be interpreted as self-inflicted wounds, such as shutting border gates for trade.

We’ll get into the newest drama later. But first, we made some maps.

Over the past 10 days, the Thai army has released visuals to support its claims to the Chong Bok/Mom Tei contested area where one Cambodian soldier was shot and killed last month.

While Cambodia early on had a more measured approach — specifically calling for the International Court of Justice to adjudicate the border in four contested areas — it has not released any maps or official photos showing its claims to the land. Cambodia has merely insisted its soldiers were stationed within sovereign Cambodian territory, with Thailand saying they were in an unresolved section of the border and should move back.

We thought we’d figure out some of this for ourselves. Here goes:

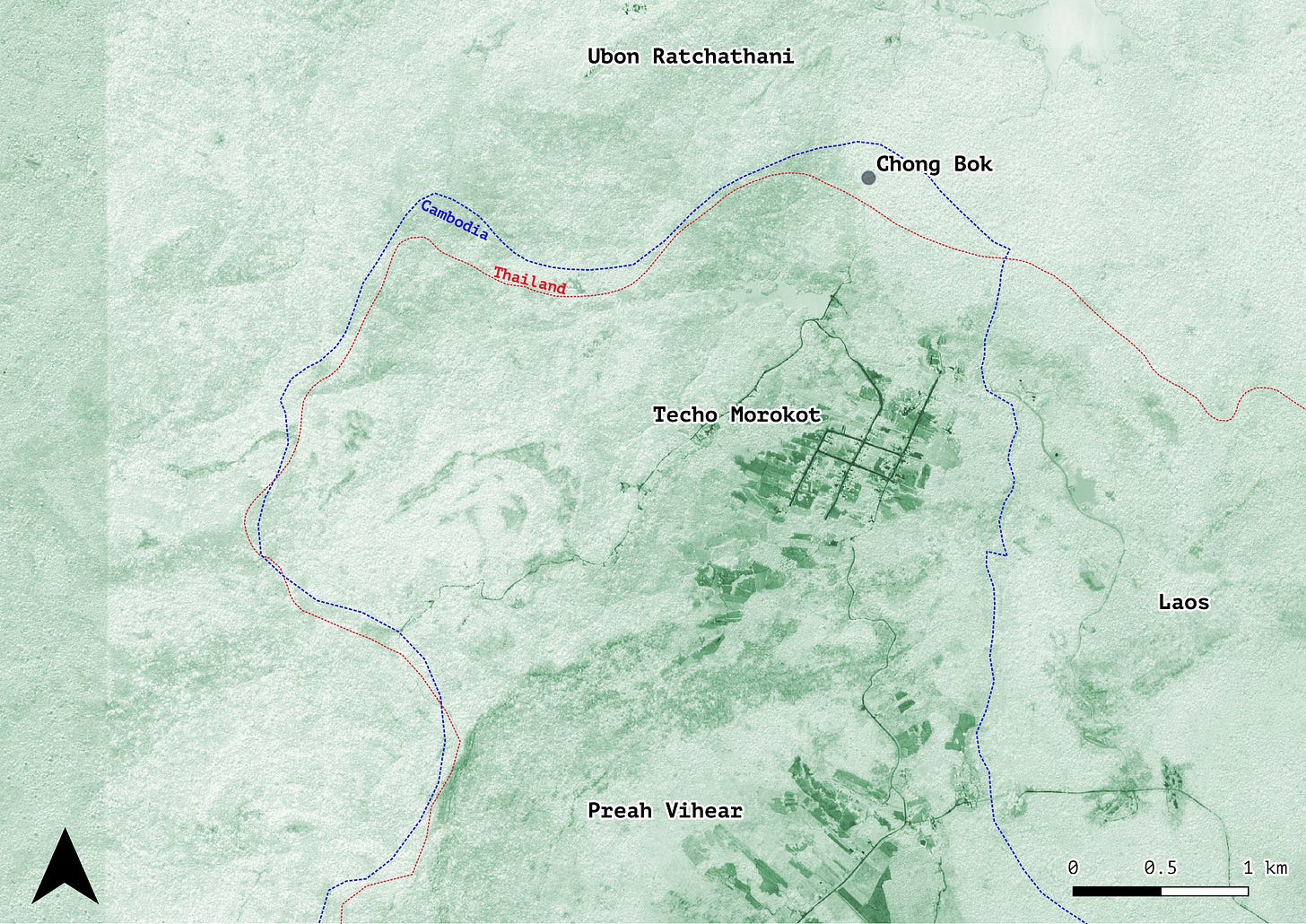

Let’s start with the Chong Bok/Mom Tei area. Looking at this map, you can see the Cambodian border line (blue dotted line) and Thai boundary (red dotted line) diverge near where gunfire broke out on May 28. (Neither side has released exact coordinates for where the Cambodian soldier was shot or where Cambodian personnel were digging a trench).

The contested land covers about 33 hectares in total and is made up of mostly forestland. To the west, the borderlines criss-cross the landscape, in some places showing that one side seems to claim less than the other side’s estimate.

Notably, there’s no temple — or other landmark — seeming to hold overt cultural or natural resource value in this disputed area, even though it’s been at the center of the recent conflict.

Here’s the Krabey temple, which features in Cambodia’s complaint to the ICJ. The Thai and Cambodian borders nearly converge in this area, placing the Krabey temple squarely in both territories. We’d wager this particular dispute will be left to expert testimony to determine the precise location of the border and which side has claim to the temple.

To the west and the east of the temple, however, are two much-larger divergences between the borders; it’s not clear if these are part of Cambodia’s ICJ complaint or not.

The most contentious area pertains to the two Ta Moan temples, where Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey province meets Thailand’s Surin province. Ta Moan Thom temple was in the news in February after Cambodian soldiers allegedly tried to sing the national anthem at the site of the temple and were stopped by Thai soldiers. In April, border liaison officers from both sides met and decided to maintain the peace.

Using available coordinates, the map shows Ta Moan Thom lies in a contested area that both sides claim to be within their territory. However, Ta Moan Touch temple, located to the northwest of its larger sibling temple, appears to be within Thailand’s claimed territory — even if one were to use the Cambodian border line. The two temples are less than a kilometer away from each other.

This area was home to artillery shelling in 2011 during the peak of the Preah Vihear dispute that started in 2008, killing at least 34 people over the course of three years.

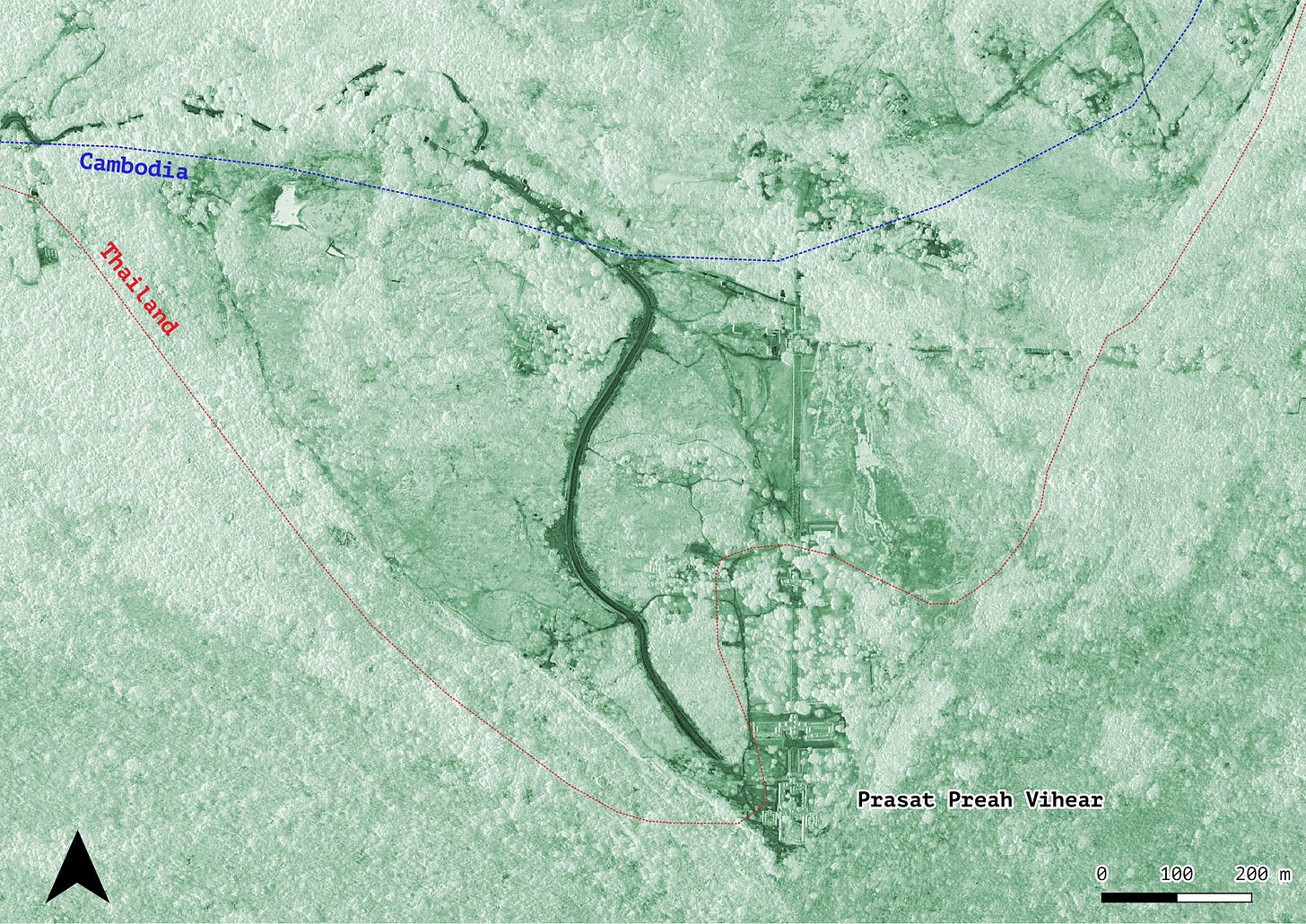

And finally, back to where it all started: Prasat Preah Vihear. As we mentioned in a prior post, the Preah Vihear decision by the ICJ in 1962 (reaffirmed in 2013) states that the temple complex lies within Cambodia. Although the court asked Thailand to withdraw its troops and military assets from the immediate area surrounding the temple, the two countries have still not clearly demarcated the border in this area.

This is important for where we’re at today. The international court said the Preah Vihear temple was in Cambodia, but it did not rule on where exactly the border should be drawn. Could this be a blueprint for Cambodia’s claim to the Prasat Ta Moan Thom, Prasat Ta Moan Touch and Prasat Krabey, in that they belong to Cambodia but the border remains ambiguous and still requires bilateral demarcation? And given that Thailand has stated that it does not recognize the ICJ’s jurisdiction in the dispute, would an ICJ decision change anything on the ground even if the court rules in Cambodia’s favor?

Given the current state of bilateral tensions, answering these questions might take years. Hopefully we can get there without a resurgence of the violence that has killed and displaced Cambodian and Thai citizens — soldiers, farmers, workers, students, tourists and traders — in the past.

On how we made these maps:

We have used international maps sourced from Cambodia in 2018 and Thailand in 2022, publicly available from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

We have used the most accurate coordinates for the four contested areas and temples from available data sources and satellite imagery. We couldn’t find officially published coordinates for the three contested temples but located them using satellite images.

Kouprey is not trying to validate claims made by either government, but we think it’s important to visualize what’s at stake in this conflict. (Please do not burn down the Kouprey stables).

Data Sources: Humanitarian Data Exchange/Cambodia - Subnational Administrative Boundaries, Humanitarian Data Exchange/Thailand - Subnational Administrative Boundaries, Google Satellite, European Space Agency.

Here are other stories on the border dispute:

— Cambodia submitted an official complaint to the ICJ over the weekend. Here are the 2013 and 1962 ruling summaries.

— Cambodia and Thailand completed their first joint border committee meeting in over a decade on Saturday and Sunday. The official Cambodian statement — pointedly, there was no joint statement — suggests the two sides discussed nothing of real substance, which was expected after Cambodia said it would not discuss the four contested areas bilaterally moving forward.

— Hun Sen raised the stakes when he said on Monday Cambodia would close all border crossings for trade if Thailand did not revert back to normal border operations by Tuesday.

— Hun Sen (and later Prime Minister Hun Manet) again asked Cambodian workers in Thailand to come back home instead of facing discrimination in Thailand. The Labour Ministry says it has 230,000 jobs for returning workers, with Kampong Speu leading the way with 63,700 jobs.

— Thai PM Paetongtarn Shinawatra spoke out against Hun Manet and Hun Sen’s use of social media and called it “unprofessional,” a rare departure from the bonhomie she has shown the Cambodian side because of her father’s close relations with the Hun family.

— Reacting to a call from Hun Manet, the Association of Banks in Cambodia and Cambodia Microfinance Association said they would “examine” how to help returning Cambodian workers who were indebted. There has been almost no acknowledgment of how a lack of well-paying jobs and soaring levels of debt have fuelled mass migration to Thailand and elsewhere.

— Cambodia followed through on a threat made by Hun Sen on Monday to stop fruit and vegetable imports from Thailand, if the Thai military did not restore border checkpoints to as they were before the conflict (aka open all checkpoints and extend operating hours).

— In an escalation from the Cambodian side, internet traffic was diverted away from Thailand and caused disruptions across the country. Border gates were ordered closed, and then opened again, affecting the flow of trucks.

— Telcos said they were obliging with the diktat for “full digital independence” and rerouting traffic away from Thailand. Energy Minister Keo Rattanak said there was enough domestic power production to withstand any Thai cuts to electricity. (Thailand had said it was considering cuts to power and internet services along border areas, where scam compounds operate, but perhaps the Cambodian government has little tolerance for measures that target criminal operations reaping billions of dollars).

— Telecom Minister Chea Vandeth claimed Thailand would lose millions of dollars over the rerouting of traffic, but had not spoken about how much telcos have spent to buy additional bandwidth to route traffic through other countries.

— While reporting on the electricity issue in Trat province, Khaosod English used a photo of sanctioned tycoon Ly Yong Phat’s Koh Kong Casino and surrounding land that allegedly belongs to him and houses a new scam annex. Both sites have seen reports of scam operations.

— In a story that came and disappeared, Thai officials said they were investigating Cambodian hackers that had defaced Thai websites over the border dispute.

— While border gate provisions have changed nearly everyday, this is what Thai officials put out last week, with both sides later making an exception for students.

— This Thai general was seemingly tired of all the rhetoric and ready for a duel.

We are acutely aware that there are way too many updates and hot takes on this dispute, and have limited these stories to encompass the major happenings of the past week. If we missed something substantial, do let us know and email us a link — we’ll note it next time around!

In local news:

— Seng Theary, Cambodian-American human rights lawyer and activist who has been imprisoned since 2022, concluded a fourth hunger strike to draw attention to jailed Cambodian political dissidents and activists. She lost nearly 7 kg over the eight-day strike before life-threatening health complications forced her to end it, according to her lawyers.— The World Bank released a recent economic update on Cambodia and it is not great: foreign direct investment crashed early this year and non-performing loan rates have reached crisis levels.

— Phnom Penh’s Chak Angre Loeu commune chief was arrested after allegedly issuing bad checks worth a total of $310,000.

— Five families in Prey Veng’s Peam Rok district lost their homes in landslides that caused the collapsing of the riverbank where their dwellings were built. Cambodia’s riverbanks have become increasingly vulnerable to collapse in recent years because of aggressive sand dredging along the Mekong River. Elsewhere in Prey Veng, a wind-heavy storm destroyed 17 more houses and ruined crops.

— Although it receives less attention in English news, local “youth gangs” allegedly involved in drugs or petty crime are projected as a huge public safety concern for many Cambodian families. In the first week of June, the Ministry of Interior reported it cracked down on 10 gangs across the country, sending at least 40 people it described as “juveniles” to jail.

— Cambodia is facing a potential travel ban from the US, which is extending an initial list of countries it placed on complete or partial bans, including Myanmar and Laos. In March, US media reported on a leaked list of countries that were likely to face travel bans, with Cambodia being placed on a “yellow list.”

Next week, we’ll send a deep-dive on the state of the Cambodian economy. (It’s not pretty). See you then!

Best summary so far in any media about the disputed land areas. It shows most vividly that not only is it not worth fighting over but a "split the difference" deal would settle the border. One thing for sure Cambodia officially should not "incite" the population. Peaceful protests are of course fine,but why are they permitted and encouraged for this cause and not for others.... actually more important, affecting many more lives? For example how many Cambodians have their land confiscated, areas in total far greater in size, land that was productive for their farming and livelihoods, in the name of development in which they do not participate?